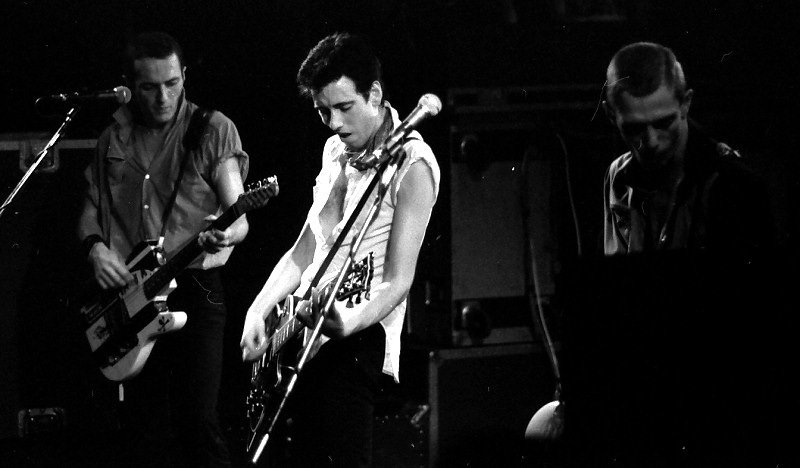

Rocking into silence with The Clash.

Why all good music is “music of the mind.”

The first big band I heard live was The Clash in Brixton, South London, back in the 1980s, when I was at school. The last, was Cage the Elephant, supported by Young the Giant, at Madison Square Garden earlier this month.

There’s nothing like a live performance. Unlike a competitive sports event, a soccer match, say, there are no sides. And strangely, the lookalike fandom element—all those kids dressed as Joe Strummer or Matt Shultz—don’t matter, and neither does the febrile merch trading that happens outside. When the music takes over, everyone is in it together, first-timers and gig-pros.

For a few hours, the world feels animated with new possibilities, even when the music’s message is rough and tough: ‘White Riot,’ ‘London Calling,’ ‘Ghetto Defendant,’ ‘English Civil War,’ and ‘Straight to Hell.’ You get the gist: Britain wasn’t in the best of shape. Paul Simonon, the bassist who apparently came up with the band’s name, was inspired by all the “clashes” reported in the newspapers. In 1981, there’d been riots in cities across the country, with Brixton a hotspot. Black youths had clashed with police, angered by a discriminatory stop-and-search policy.

The Brixton Academy (briefly the Brixton Fair Deal), built in the 1920s, originally as the Astoria Variety Cinema, isn’t a large venue by contemporary standards. And at The Clash concert, we were up close to the stage, pogoing as the furious music, all 100 plus decibels of it, powered through our lanky frames.

One side effect was a partial loss of hearing, at least for 24 hours. The world came with a background buzz, like the sound of a dead TV back in the day when channels shut down for the night after the national anthem. And even when we were still, it felt as if we were one step from terra firma, teetering down a gangplank from a ship at sea.

At the Cage the Elephant concert, my apple watch kept flashing me “loud noise” notifications with the panicky insistence of an over-protective parent, telling me to get out or go deaf.

There’s a paradox, here, in that while I’ll pay to listen to sensorineural-shattering music, I’m also in perpetual pursuit of silence. This isn’t a question of taste or prejudice, as in the sounds I make are music, whereas your sounds are noise. Or some NIMBY protestation based on the assumption that my noise is acceptable, but yours sucks.

Outside of a rock concert, I’ll wear headphones when I turn up the volume, conscious that others might not like or wish to hear what I play. Because I know what it’s like to live with unwanted sounds seeping through the cracks of a sleep-deprived consciousness as insidiously as water or hibernating rodents.

In the 1990s, we lived in London above an actress who seemed to be hosting an interminable party. The day she moved in, she watched Oliver Stone’s movie, The Doors, cranked up so the floorboards shook, and Val Kilmer’s Jim Morrison boomed like a born-again Batman through the pipes. This was “break on through to the other side” literally interpreted. When Kilmer-Morrison hollered in his mic to a background of screaming fans, “Is everybody in, the ceremony is about to begin!” we guessed what was coming: noise, lots of it.

When we first moved to New York City, the couple in the house next door would have intermittent, drink-fuelled door-slamming and glass-throwing rows, while the psychotherapist in the converted cellar downstairs played 1960s vinyls as if his life depended on it. ‘Here Comes the Sun,’ will never sound the same.

Hong Kong, though, was the worst place when it came to noise, which is hardly surprising given that seven million people live on top of each other, which might make it one of the most sustainable cities on the planet but gives it a high decibel rating. On the thirty-third floor of our apartment in Mid-Levels, we were surrounded by near constant brain-addling drilling from renovation work, while the neighbor above would keep us up until the early hours, torturing Bach’s Prelude in C Minor on a digital Yamaha. One of my students, who lived on a public housing estate in Kowloon, wrote a dissertation on noise inspired by his own experience of sleep deprivation.

All this noise has made silence an exclusive commodity. Noise-elimination today is a booming business, from the luxury of hushed getaways to noiseless dishwashers. Meanwhile, the search for quietude has a long history within spiritual and philosophical traditions. As does noise control. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as industrialization transformed living, ordinances were passed to curb noise “nuisances,” and a plethora of new organizations arose dedicated to the cause, such as the Society for the Suppression of Unnecessary Noise, founded by Julia Barnett-Rice in New York in 1906. At the same time, innovations in recording, broadcasting, and monitoring sound created a new sensitivity to the audible. Stethoscopes allowed physicians to listen to the body’s inner workings, the phonograph—invented in the 1870s—enabled sound to be captured, while hearing-aids were introduced from the 1880s.

It’s true that some people are unphased by noise. Among them was the Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca, who had lodgings over a public bathhouse and could hear “every kind of sound” from below, including “the smack of a hand pummeling” a client’s shoulder, or a “brawl” when someone was caught thieving. “I cannot for the life of me see that quiet is as necessary to a person who has shut himself away to do some studying as it is usually thought to be,” he wrote. Only the dead were silent, not the living.

But then noise has always had its champions, and silence its detractors. Take the latter. While noise may be linked to an exhilarating modernity, as a political metaphor, it tends to be equated with censorship and tyranny, invoking a world in which the voices of discriminated social groups are squelched, or they’re told to keep “silent unless spoken to,” or to be “seen and not heard.”

Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, suggested that silence was a form of unhealthy repression, a theory that was to be hugely influential in the twentieth century. In the 1960s, efforts to break repressive silence gained momentum. Arguments about the restorative effects of “speaking out” and the frustrations of the “silent majority,” became commonplace from politics to psychology and ecology (Rachel Carson’s book ‘Silent Spring’ came out in 1962).

As I walked out of Madison Square Garden, negotiating the crowds by Penn station with that familiar post-concert tintinnabulation in my ears, I wasn’t reflecting on this intricate noise history, so much as thinking how attentive the music had made me to the city and its commotions. A few months before, I’d seen the Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind exhibition at the Tate Modern in London. “The only sound that exists to me,” she’d written, “is the sound of the mind. My works are only to induce music of the mind in people … In the mind-world, things spread out and go beyond time.” It struck me, then, that all good music—the Brixton Clash gig included—is at its root “mind music,” in that its riffs diffuse through time, far beyond the thrill of the live, ear-splitting performance. So that even now, decades later, the music in my head makes room for an unexpected calmness amid the clamor of the everyday.